I have been thinking about wells lately. Not the kind you draw water from, but the other kind — the deep, dark spaces where we throw things we do not want to examine too closely. Memory has a way of becoming a well like that, especially when the memories involve things like war, guilt, and the particular weight of choices that can’t be undone.

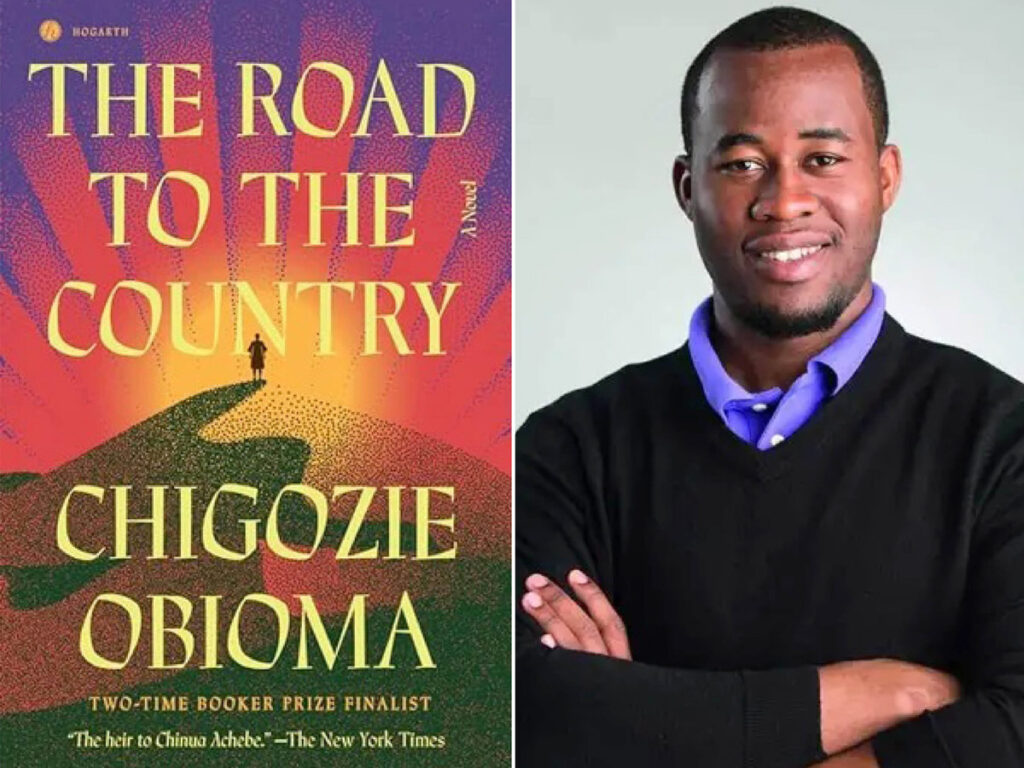

Chigozie Obioma’s ‘The Road to the Country’ is a novel about a young man named Kunle who spends most of his time trying to climb out of such a well, only to find that the war raging around him keeps making it deeper. It is set during the Nigerian Civil War of 1967-1970, though the war feels less like a historical backdrop than like a vast, indifferent machine designed to turn ordinary people into strangers to themselves.

The novel opens with a mystical framework: a Yoruba seer in 1947 witnessing visions of events that would unfold twenty years later. This seer appears throughout the book in interludes, watching Kunle’s story unfold like someone helplessly observing a car accident in slow motion. The idea is intriguing — what if prophecy was less about divine knowledge than about being trapped in an endless loop of terrible foresight?

But here is where the novel encounters its first significant problem. The seer’s sections, while atmospherically written, become repetitive. Too often, we find him “watching” and “not understanding” without the imagery or emotional development that made the opening vision compelling. By the novel’s middle sections, these interludes feel like interruptions rather than deepening mysteries. The mystical framework, instead of adding cosmic weight to Kunle’s suffering, sometimes feels like an elaborate way to avoid grappling directly with the war’s human realities.

When the framework works, as when Kunle hears the seer’s voice cry “Turn back!” during his near-death experience, it achieves genuine uncanniness. But too often, it serves as emotional insurance, providing metaphysical significance to events that might carry more power through their stark human truth alone.

What Obioma understands perfectly is how war transforms people not through dramatic conversion but through the accumulation of small compromises. Kunle begins as a guilt-ridden university student searching for his disabled brother, Tunde. Through a series of mishaps, he becomes conscripted into the Biafran army, where his identity as ‘Kunle’ gradually gives way to ‘Peter Nwaigbo’, the name his captors assign him.

The novel’s strongest passages occur during this transformation. Obioma captures the texture of military life — the exhaustion, the gallows humour, the way friendships form under extreme duress — with remarkable authenticity. The friendship between Kunle, Felix, Bube-Orji, and Ekpeyong develops organically, providing moments of genuine warmth that make their eventual losses genuinely devastating.

Particularly effective is Kunle’s moral awakening to the Biafran cause. Rather than presenting this as a simple conversion, Obioma shows how witnessing civilian casualties during air raids gradually shifts Kunle’s perspective from unwilling participant to someone capable of choosing solidarity. This avoids both naive patriotism and cynical detachment.

However, the novel struggles with its protagonist’s psychological patterns. Despite experiencing profound trauma and significant character development, Kunle’s internal monologue returns obsessively to the same guilt over his brother’s childhood accident. While this repetition is psychologically plausible, it creates a circular quality that limits narrative momentum. We understand Kunle’s guilt after the first few explorations; the continued dwelling feels less like psychological realism than like an authorial reluctance to let the character evolve.

Obioma writes war with unflinching detail. His descriptions of corpses, decomposition, and battlefield chaos demonstrate both historical knowledge and genuine commitment to showing war’s full cost. The battle sequences, particularly the collapse at Eha Amufu and the hellish bombardment at Abagana, achieve visceral power that makes the reader understand why trauma fractures memory and identity.

But the novel’s commitment to comprehensive documentation sometimes becomes counterproductive. Extended passages cataloguing various forms of mutilation and decay risk numbing rather than horrifying the reader. Obioma’s prose, while often beautiful, can become overwrought in these sequences. When he writes that “The vehicle blunders into the undergrowth, tugs blindly to one side, and jerks to a stop like an old hog shot through the heart,” the elaborate metaphor calls attention to itself rather than serving the scene’s emotional needs.

The novel works best when its descriptions serve psychological rather than merely documentary purposes. Kunle’s hallucination of his soul leaving his body during the bombardment, or his encounter with testimonies from the war dead during his near-death experience, uses surreal imagery to approximate trauma’s effects on consciousness. These passages feel necessary rather than excessive.

The relationship between Kunle and Agnes, the female corporal who becomes his lover, provides some of the novel’s most tender moments. Obioma handles their physical intimacy with restraint, showing how war creates a desperate need for human connection while constantly threatening loss.

Yet Agnes herself remains largely filtered through Kunle’s perspective. We learn about her past — the massacre of her family that drives her thirst for vengeance — but primarily as information that explains her effect on Kunle. Her own interiority, her specific way of processing trauma and choosing to continue fighting, remains underdeveloped.

This becomes particularly problematic given her ultimate fate. Agnes dies in combat while Kunle has deserted, a tragedy that provides the novel’s emotional climax. But because we know her primarily through Kunle’s eyes, her death feels more like a blow to his development than a loss of a fully realised character. The novel misses an opportunity to explore how trauma affects women differently, how female soldiers navigate spaces traditionally coded as masculine, or how Agnes’s specific history shapes her choices.

‘The Road to the Country’ covers three years of war, which proves too much material for coherent narrative treatment. The novel’s length, necessary to show war’s grinding effects, creates pacing problems where individual battles blur together. A more focused temporal frame might have allowed for deeper psychological exploration.

The novel also struggles with scope. While Obioma gestures toward exploring non-Igbo minorities caught between opposing forces, different generational perspectives, and foreign intervention, these threads remain underdeveloped. The focus necessarily remains on Kunle’s individual journey, but this sometimes makes the broader context feel sketched rather than fully inhabited.

The ending, where Kunle meets his daughter and accepts responsibility for her, provides emotional resolution while suggesting cycles of inheritance and witness. But it arrives after considerable meandering through post-war devastation that, while historically accurate, tests the reader’s patience.

Despite these flaws, ‘The Road to the Country’ succeeds in ways that matter. Obioma’s decision to narrate the Biafran War from a mixed Yoruba-Igbo perspective provides valuable objectivity on events that remain politically sensitive. His portrayal of how ordinary people become complicit in violence they barely understand speaks to contemporary conflicts worldwide.

The novel’s documentation of specific textures — the improvised weapons, the constant hunger, the makeshift hospitals — creates an important historical record. Obioma’s research appears thorough, and his details ring true to accounts of the conflict.

Most importantly, the novel grapples seriously with questions about witness and testimony. How do we bear witness to experiences that exceed comprehension? What do we owe to those who died in conflicts we survived? How do we pass along knowledge of trauma without perpetuating its cycles?

These questions do not have easy answers, and Obioma resists providing them. The seer’s progressive blindness, losing his prophetic gift precisely because he interfered when he should have only watched, suggests that witness carries its own costs and limitations.

‘The Road to the Country’ is a flawed novel that tackles essential subjects. Its repetitions, its occasional purple prose, and its structural imbalances prevent it from achieving the masterpiece status that seemed within reach. But at its best — in its portrayal of friendship under extreme circumstances, in its refusal to romanticise either war or resistance to war, in its commitment to showing rather than explaining trauma’s effects — it provides insights that will disturb readers long after finishing.

The novel reminds us that some experiences can only be approached obliquely, through accumulated approximations rather than direct representation. In doing so, it performs the essential function of serious literature — maintaining space for questions that would otherwise disappear into the silence we mistake for peace.