Gender identity in literature does not always announce itself loudly. In some works, by female writers, it creeps into narrative spaces, revealing itself through silence, endurance, emotional labour and the everyday negotiations women make within culture and tradition. Rather than foregrounding gender as a declared theme, these writers often allow it to emerge gradually, embedded in language choices, character experience, and narrative movement. Gender, in this sense, is not a fixed category but a lived condition constructed through social expectations, cultural norms, and personal history.

Many people confuse sex and gender: sex is a biological trait, while gender is shaped by society, language and power. Feminist thought has long argued that womanhood is not merely biological but socially formed. On the other hand, literature gives us an intimate terrain where those ideas are felt rather than merely stated. In storytelling, female writers inscribe gender identity subtly, allowing readers to encounter womanhood as experience rather than ideology. The researcher recognises this same impulse in his own writing: an artistic piece often carries the burden of what we have seen or felt, and the story becomes a vessel for that quiet memory.

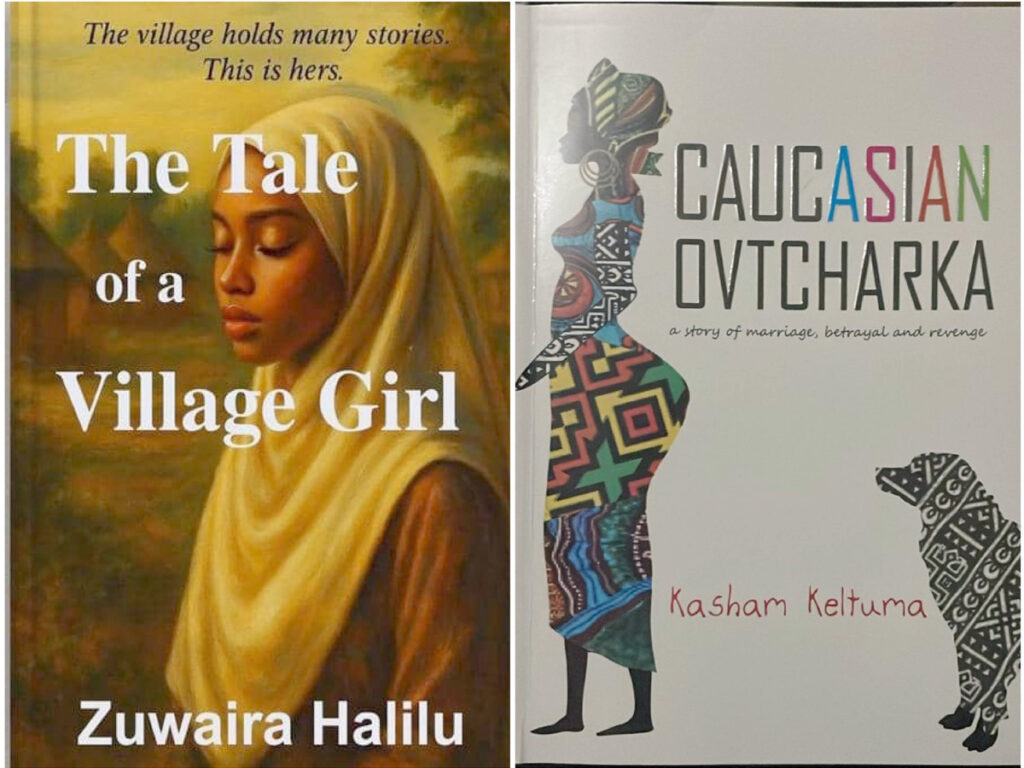

This essay situates itself at the intersection of language, culture, and tradition. It examines how gender identity operates quietly within two contemporary Nigerian texts: Caucasian Ovtcharka by Kasham Shawanma Keltuma and The Tale of a Village Girl by Zuwaira Halilu. Though different in setting and tone, both texts trace female journeys shaped by cultural expectations, loss, denial, endurance and the search for selfhood. One narrative ends in tragic rupture; the other in quiet survival. Together, they reveal how gender identity creeps into narrative not through proclamation, but through lived reality.

Womanhood, as presented in much female writing, is rarely static. It is formed socially, negotiated emotionally, and performed within cultural boundaries. A woman becomes herself through experience: through what she is allowed to desire, what she is denied, and what she is expected to endure. Gender identity, therefore, emerges not as an abstract idea but as a continuous process shaped by language, silence and responsibility. Silence plays a crucial role in this construction. In many cultural contexts, especially within African societies, women are socialised to endure quietly. Silence becomes both a survival strategy and a burden — it holds pain, obedience, resistance, and sometimes rebellion. Emotional labour, the invisible work of caring, maintaining harmony, and suppressing personal desire, is another marker of gendered identity. Women are expected to absorb emotional weight for families, marriages and communities, often without recognition; the narrative itself becomes a site where gender is performed.

Through the researcher’s point of view, pacing and attention to inner life, female writers encode womanhood into the very structure of storytelling. What the text emphasises, omits, and allows to unfold slowly all contribute to how gender identity is revealed. Rather than declaring “this is a woman’s struggle,” the text allows readers to experience it, to live inside the small gestures and the unsaid moments. Feminist thought provides useful lenses, even when the texts resist over-theory. The idea that gender is constructed, performed, and relational helps to read these novels without forcing them into doctrinal categories.

The writers examined here do not offer manifestos — they offer lives. The theoretical anchor for this essay is therefore pragmatic: gender in these stories is constructed through everyday practices, language, ritual, duty, and silence, shown rather than argued. This approach allows us to read Keltuma’s and Halilu’s novels attentively to interior life, sensitive to cultural texture, and alert to how tiny narrative choices express gendered belonging.

Caucasian Ovtcharka is a layered, satirical, and emotionally intense work that exposes hypocrisy, religious gluttony, and cultural dilemmas while tracking an intimate human tragedy. At its centre is a young woman whom the researcher chooses to call Mariam for clarity, since her name was never mentioned. She is forced into a marriage not of her choosing. She loved someone else (Mathias), but her father had already laid out her future; her true preference was summarily dismissed. This denial of love is the first instance in which patriarchal control writes itself onto her life.

Compounding the problem is her husband’s physical disability: he walks with a default in his leg. This detail is more than description; it reshapes domestic dynamics. Where independence might normally be expected of a spouse, Mariam instead becomes a caregiver by structural design. Her husband’s physical challenge complicates their intimacy and creates an uneven terrain of obligation. He is physically dependent; she is emotionally suffocated. The novel uses sharp writing and satirical strokes to show how religious piety, social respectability, and family pride can camouflage cruelty. The household becomes a theatre of spiritual manipulation and moral contradictions: pious language sits uneasily beside selfishness and greed.

Keltuma’s voice here is candid; the stylistic energy is part of how gender creeps into the novel, that is, the pressure of the world is felt in terse dialogue, in sudden images, and in the quick, stinging asides that reveal the wife’s constrained horizon.

Valentine, the deformed but noble dog gifted to Mariam, is the story’s most charged symbol. He is not only a companion but a witness, a living mirror to Mariam’s own marked condition. Like her, Valentine bears what the world treats as a defect: yet he is loyal, dignified and capable of love. Readers have noticed how the dog’s unconditional presence exposes the emotional paucity of human relations in Mariam’s home. Where humans withhold empathy, Valentine offers the steadiness of non-judgmental affection. The dog becomes the locus of a different ethics, one that contrasts sharply with the household’s hypocrisy.

Keltuma’s text is also a social critique. By satirising religious gluttony and mocking social pretence, it unmasks the way cultural institutions protect the powerful and curtail the vulnerable. In Mariam’s story, gender identity is not a banner or programme; it is the quiet architecture of obligation. Through details, tone, and symbol, the novel demonstrates that being a woman in such a world is often a matter of endurance until endurance becomes unbearable. The narrative closes on a devastating note — Mariam kills herself. Her suicide must be read within the book’s logic. In a life where every meaningful decision of marriage, role, and obligation was arranged by others, death becomes the final assertion of agency. It is a tragic reclaiming of authorship over her life when every other avenue is blocked. The act does not glamourise death; it indicts a system that offers no dignified exit. Here, gender identity culminates in rupture because the social architecture denied incremental selfhood.

On the other hand, Zuwaira Halilu’s The Tale of a Village Girl is quieter by temperament but no less radical in its attention. The protagonist, Salmah, is the lastborn child in a family with two elder brothers. Her vulnerability is heightened by loss. Her mother dies in childbirth, and a week later, her father dies as well. Orphaned at birth, Salmah is cast early into dependency and responsibility. Her story is propelled less by conventional ambition than by the necessity of survival and self-preservation.

Halilu’s prose moves with a gentle, lyrical cadence. She lingers on small domestic details, the scent of fresh cassava, the hush of dawn crafting a sensory world that roots Salmah’s identity in place. The village represents origin, community, and a rhythm of belonging. Yet, that very rootedness also carries strict expectations for girls’ humility, obedience and emotional restraint.

The narrative carefully shows how culture shapes what a girl can imagine for herself. Salmah’s migration to the city is not only spatial but symbolic. The city is an unfamiliar landscape of compressed rooms, crowded markets, and new social codes. For Salmah, the move is both dislocation and possibility. The village has shaped her, but the city offers the chance to develop an identity beyond the borders of inherited routine. Crucial here is that Salmah’s becoming is gradual. She does not stage dramatic rebellion; she adapts, learns and quietly asserts herself. Her resilience is unshowy but steady.

The novel also introduces forced marriage through a close friend, often called Ladidi (Salmah’s bosom friend), who is compelled to marry an older man. This sub-plot resonates with painful particularity — it speaks to how female bodies are negotiated in the name of family advantage and honour. To the reader who has lived near such realities, the prose carries a tangible ache.

Halilu does not sensationalise; she encounters such scripts with empathy and precise observation. The risk Ladidi faces sits like a shadow close to Salmah’s own life, reminding us that structural threats are seldom distant, thus would have been Salmah’s fate as well, although her parents like education. Salmah’s trajectory, therefore, becomes a model of survival and self-formation within constraint. Rather than announcing a programme for liberation, the novel honours the interior work of growing into oneself. The culture that teaches silence and deference is not simply condemned; its textures and comforts are also acknowledged. Halilu’s approach is humane. She renders the village’s warmth and the woman’s inner resources with equal care. Gender identity here is shaped through patience, memory, and the steady accumulation of small choices that amount to a life.

Keltuma’s account of how a single, memorable encounter with a big, silent dog stayed with her for years, and supplies the germ of Valentine’s presence. Her stated belief in balanced gender equality, one that prizes dignity and practicality rather than theatrical rhetoric, aligns with the novel’s refusal to be a polemic. Similarly, Halilu’s background in education and humanitarian work clarifies why her prose attends to the village’s textures and to social vulnerability without sentimentalising them.

Reviews from friends like Mr Temitope and Miss Ruth praised Keltuma’s voice as energetic, candid and original. Others said the book “hooks” the reader with a compelling interplay of greed, suspicion and love. These reactions show how the novel’s satirical energy amplifies its moral critique. On Halilu’s side, the emotional honesty of Salmah’s journey adds to the narrative’s tender regard for the village’s textures. Seeing Ovtcharka as satire that ridicules hypocrisy and religious gluttony, and recognising the novel’s feminist and socio-psychological layers.

Reading together, Caucasian Ovtcharka and The Tale of a Village Girl, create a powerful comparative space for examining the subtle formation of gender identity within language, culture and tradition. Neither text declares gender as an overt ideological project; instead, both allow it to surface through lived experience, through what women endure, suppress, negotiate and, in one case, finally reject. Gender, in these narratives, is not announced with banners or slogans but constructed through the rhythms of everyday life, domestic expectations, emotional labour and cultural silence. It is in this quiet unfolding that the true politics of womanhood emerge.

One of the most striking threads connecting both texts is endurance, though its outcomes differ radically. In Caucasian Ovtcharka, endurance is corrosive. Mariam’s obedience, her forced acceptance of a marriage she did not choose, and her role as emotional and physical caregiver to a disabled husband, accumulate into a suffocating burden. Her silence is not passive; it is coerced, trained, and demanded by a patriarchal structure that offers her no genuine reciprocity. Over time, this endurance ceases to be virtuous and becomes lethal. The novel insists that there are limits to how much a person can absorb without rupture, and Mariam’s tragic death marks the point at which endurance collapses into self-annihilation.

By contrast, endurance in The Tale of a Village Girl is adaptive and sustaining. Salmah’s patience, shaped by orphanhood and early loss, becomes a survival strategy. Rather than erasing her, endurance slowly remakes her, allowing her to negotiate space for belonging, dignity, and self-definition. What destroys one woman becomes a resource for another, revealing how gender identity is shaped not only by constraint but by the possibilities available within it.

This contrast sharpens further when the texts are placed along the axis of death and survival. Mariam’s suicide in Caucasian Ovtcharka is not a narrative shock device; it is the tragic centre of the novel’s moral argument. It represents the final assertion of agency in a life where every meaningful decision has been outsourced to cultural authority, father, marriage, religion and social expectation. Her death exposes the violence of a system that leaves women no legitimate space to live fully as subjects. Salmah’s journey, on the other hand, is one of survival that preserves dignity. Her world is harsh, but it allows for relationships with chosen kin, communal ties and quiet solidarities that enable her to continue. The divergence between death and survival demonstrates that gender identity, even under patriarchal pressure, is not monolithic; it is shaped by degrees of access to care, mobility and belonging.

Silence operates as a shared but differently inflected language in both novels. In Caucasian Ovtcharka, silence is the accumulation of pain, the unsaid that thickens until it fractures the self. Mariam’s quietness is not contemplative but enforced, a condition that denies her voice and ultimately her life. In The Tale of a Village Girl, silence performs a protective function. It shelters Salmah’s interior life, allowing her to observe, learn and endure without immediate exposure. Here, silence becomes reflective rather than explosive, a space in which growth can occur. Both texts remind us that silence is not the absence of meaning; it is saturated with cultural instruction and emotional consequence. It is one of the primary languages through which gender is learned and lived.

Symbolism deepens these constructions without overt theorising. Valentine, the dog in Caucasian Ovtcharka, embodies unconditional loyalty and emotional constancy in a world that denies Mariam empathy. His presence exposes the hollowness of human relationships governed by duty rather than care. Like Mariam, Valentine carries what society perceives as a defect, yet he is capable of profound affection. The village landscape in The Tale of a Village Girl performs a different symbolic function. Its open skies, familiar routines, and communal memory ground Salmah’s identity, even as she moves into the complexity of urban life. Objects and spaces, an empty chair, a remembered courtyard, a quiet room store gendered meanings of loss, desire and deferred possibility. These symbols hold what the narratives refuse to explain outright.

Form and tone further reveal the politics of gender in both texts. Keltuma’s prose is sharp, sometimes biting, marked by satire and urgency. Her language exposes hypocrisy and moral gluttony with deliberate force, mirroring the emotional claustrophobia of Mariam’s life. Halilu’s prose, by contrast, is patient and lyrical, inviting the reader to dwell in texture, memory and gradual transformation.

These stylistic differences are themselves gendered acts of expression. Each writer produces gender identity through craft, through pacing, imagery and attention to interiority, insisting that lived experience, not argument, be taken seriously as a site of knowledge.

Authorial contexts subtly reinforce these readings. Keltuma’s translocal experience, shaped by movement between Gombe State and Canada, informs her sensitivity to cultural contradiction and emotional displacement. Her account of encountering a Caucasian Ovtcharka years before writing the novel illustrates how a single image can incubate meaning over time, eventually crystallising into a metaphor. Her commitment to balanced gender equality and fairness without theatricality aligns with the novel’s refusal of caricature. Halilu’s background as an educator and humanitarian worker is audible in her ethical restraint and layered empathy. Her handling of orphanhood and forced marriage avoids sensationalism, favouring careful observation and structural awareness.

The authorial notes and reader responses one gathers are therefore not peripheral. They confirm that intention and reception converge around the same recognition of gender’s subtle presence. Reading these texts also demands ethical attentiveness. Mariam’s suicide must not be aestheticised or reduced to a symbol alone — it is a symptom of sustained social failure, the endpoint of many small acts of violence. Likewise, the forced marriage of Salmah’s friend calls for steady empathy rather than simplified judgment.

Both novels refuse easy solutions, acknowledging that cultural change is slow and uneven. Their ethical power lies in witnessing and making visible the conditions under which suffering becomes ordinary. Gender in these works does not exist in isolation. Class, region, religion, and physical ability intersect with womanhood to shape lived realities. In Caucasian Ovtcharka, religious pretence and social respectability protect cruelty, while disability complicates masculine authority. In The Tale of a Village Girl, rural precarity and urban anonymity create different fields of vulnerability and opportunity. These intersections remind us that gender identity is always entangled with other forms of difference.

Taken together, Caucasian Ovtcharka and The Tale of a Village Girl affirm that gender identity in female writing often creeps rather than declares. It lives in endurance and silence, in symbols and spaces, in the slow negotiation between self and society.

Why should we attend to the subtle creeping of gender identity in these novels? There are practical implications for readers, teachers and policy makers. For readers, sensitivity to subtle gender cues develops empathy and averts reductive readings that either romanticise suffering or dismiss everyday endurance. For teachers, these novels provide pedagogical entry points into discussing gender, tradition, and agency without relying on polemical texts that may alienate students. For community workers and policy makers, literary attention to the quiet textures of women’s lives can inform nuanced interventions that respect cultural difference while protecting rights and bodily autonomy.

Finally, Caucasian Ovtcharka and The Tale of a Village Girl contribute profoundly to contemporary Nigerian literature by articulating womanhood as lived experience rather than declared ideology. Keltuma and Halilu do not shout feminist slogans; instead, they allow readers to feel the weight of womanhood through diction, rhythm, silence and domestic detail. Their works confirm that gender identity is constructed within language, culture and tradition, and that literature remains one of the most powerful spaces for revealing these subtle truths.

Both novels treat the body as a site of learning and performance. Gender is enacted through gestures, labour, posture and restraint. Mariam’s domestic routines, her controlled movements and suppressed desires are bodily inscriptions of expectation. Salmah’s adaptability, the way she learns to move through the city, to work, to endure, becomes a series of micro-performances that accumulate into selfhood. Gender here is not merely spoken, it is done. To understand women’s lives, we must listen closely not only to what is said, but to what is endured in silence. The power of a smile, a pause or a gentle act of kindness can speak louder than any public declaration.

In reading Salmah and Mariam, the researcher felt kinship with their struggles and a renewed sense that representation often lies in nuance. The stories whisper a powerful message, being a woman is lived in acts of care, endurance and hope, and sometimes the most profound statements are made in silence.

Caucasian Ovtcharka (literary fiction, 193 pages) by Kasham Shawanma Keltuma. Published in 2025 by Kasham Keltuma.

The Tale of a Village Girl (literary fiction, 108 pages) by Zuwaira Halilu. Published in 2025 by Kairos Tablets and Scrolls.

Ogba Favour Precious, born on 12 August, hails from Isoko South Local Government Area of Delta State. He holds a B.A. in Theatre Arts from the Federal University, Lokoja. A passionate writer and critic, his engagement with writing began during his secondary school years. Beyond writing, Favour is a versatile theatre practitioner and accomplished dancer, lighting engineer, director, and actor. He has authored several critical essays, including Female Reality and When the Stage Calls, When the Stage Speaks: Sociopolitical Reconstruction in Rogbodiyan. He currently serves as the Librarian of the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), Kogi State Chapter, and emerged as the fifth runner-up in the 2025 Ngugi Project (CORA). Presently, he works as a teacher at Future Start Academy.