I read novels the way some people listen to rap, half-focused, following the rhythm until something stops me cold. A phrase. A character who reminds me of someone I knew once, or thought I knew, or dreamed about. This is not efficient. But efficiency has never been the point of reading.

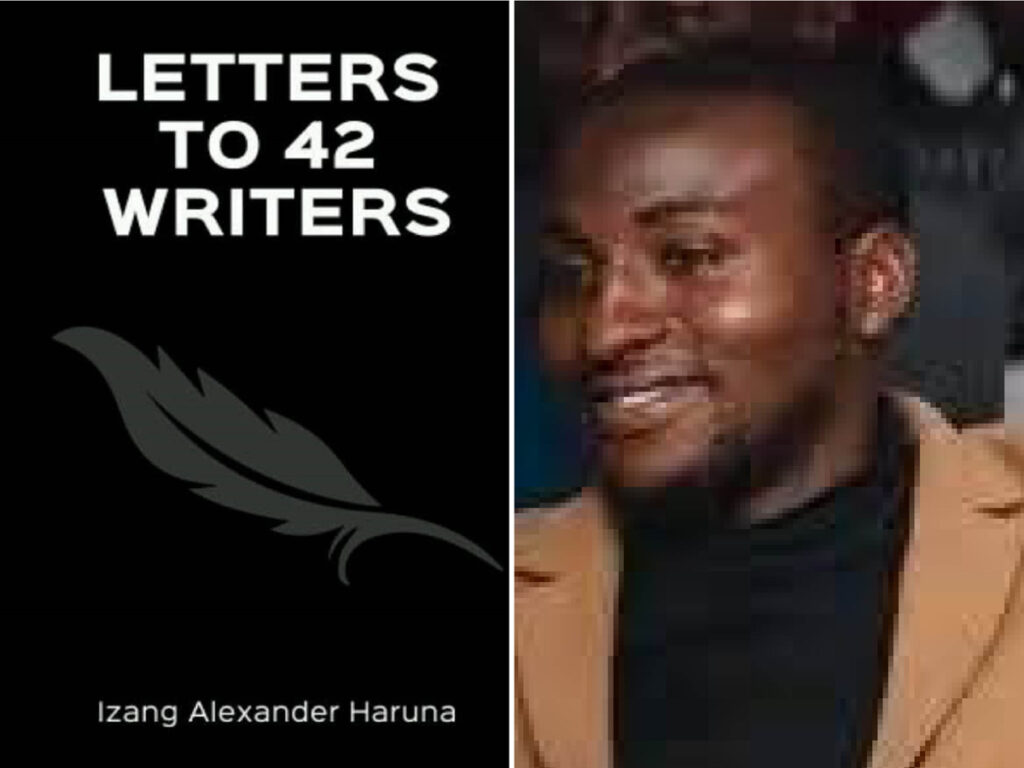

So, there I was, reviewing a novel whose title I have already forgotten, when I noticed something in my inbox. A file I had been sent weeks earlier — maybe three, maybe four — sitting there like a cat that had been waiting patiently for me to come home. Letters to 42 Writers by Izang Alexander Haruna. A bonus book the author had sent while we shared recommendations on craft. I had thanked him for the main book but completely missed this one. Just scrolled right past it.

You know that feeling when you realise that you have been rude without meaning to be? That hollow drop in your stomach? I felt that. Then I felt something else: curiosity strong enough to make me abandon the novel I was supposed to be reviewing. This should have been my first clue that something strange was happening.

By Wednesday, I had finished it. By Thursday, I could not stop thinking about Chapter 18, where Deborah flips the whole script and says writing discovers you, not the other way around. By Friday, I was making pap at 4 a.m., not because I had to, but because I wanted to write this review before the feeling evaporated.

Murakami once said he wakes up at 4 a.m. and writes for five to six hours when working on a novel. I am not disciplined like that. But this book made me want to be.

There is something happening in Jos, Nigeria. Something in the water or the air, or maybe just in the small community of writers who gather there and refuse to treat writing as anything less than sacred work.

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, who won the 2016 NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature for Season of Crimson Blossoms. A tradition of making art that matters, that lasts, that refuses the laziness of thinking good writing just happens. And now Izang Alexander Haruna, philosopher and criminologist turned literary critic, adds his voice to that lineage.

But here is what makes Jos different: they do not just produce good writers. They produce writers who think about writing. Who treat craft like something worth studying the way scientists study cells or physicists study particles. The Twelfth Despatch Fellowship — 100 young writers from all six geopolitical zones of Nigeria gathering in a WhatsApp group to discuss style, craft, the rudiments of good prose — this is the kind of intentionality that most literary communities talk about but never actually do.

Forty-two of those writers submitted essays. And Izang, who had facilitated one session on Leonardo da Vinci’s biography, decided to reply to each one. On Facebook. One per day. Consecutively. For 42 days.

Nobody asked him to do this. The fellowship was over. He could have just moved on. But he did not. And the editorial team, watching these replies accumulate like pearls on a string, secretly collected them, formatted them, and only told Izang after they had assembled the manuscript. By the time Izang saw what they had done, it was already a book. This is the kind of thing that only happens in places where community still means something. Where writing is not just a career move but something closer to worship.

Letters to 42 Writers is structured like a rap composition. There is a melody (the theme of becoming through writing), but each chapter riffs on it differently. Murakami learned the importance of rhythm from music, mainly from jazz, noting that style needs good, natural, steady rhythm, or people would not keep reading. Izang does the same thing here, except with ideas instead of melody.

Chapter by chapter, the book accumulates weight. Not the dead weight of academic prose, but the living weight of ideas that keep circling back, deepening, complicating themselves.

Vigil (Prologue) introduces writing as kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold. The cracks become the beauty. Desire(Chapter 2) elevates writing to nobility, a sacred burden that weighs on those who carry it. Micah (Chapter 3) grounds everything in scripture: “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word…” Writing as sustenance, as that which keeps us alive.

By the time you reach Deborah (Chapter 18), the book has taught you a new way of seeing. She argues that we do not discover writing — writing discovers us. Like Copernicus flipping the cosmos so that the earth orbits the sun instead of the other way around, Deborah flips the writer-writing relationship. Suddenly, everything makes sense in a way it did not before.

This is what the book does best: it does not just talk about writing. It enacts transformation through the very act of epistolary exchange. Izang listens, really listens, to these 42 young writers, then reflects their ideas to them with enough philosophical weight that they can see their own thoughts as something valuable, something that matters.

There is a scene in Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore where the protagonist, a 15-year-old runaway, spends days in a library reading, and in those reading sessions, he becomes something he was not before. Not suddenly, but gradually. The way snow accumulates. That is what these 42 letters do. Each one is a small accumulation. Hope (Chapter 19) calls journaling a “war room”, a sacred space for fighting inner battles. Nendirmwa (Chapter 21) writes as a deaf person, describing how writing bridges the disconnect between her world and the hearing world. Angel (Chapter 20) describes her father refusing to publish her first collection, and only later realising the refusal was a gift, a furnace that refined her into gold.

These are not abstractions. They are lives. And Izang, with his training in philosophy and criminology, his academic precision, and his generous heart, meets each writer where they are. Sometimes with Aristotle and Schopenhauer. Sometimes with scripture. Sometimes with stories from other fellows in the anthology, weaving connections that show these 42 people are not just writing to Izang, they are writing to each other across the book’s architecture.

By Nyinrotmwa (Chapter 36), the book has become a fugue. Voices layering over voices. Metaphors echoing. Osaume’s dance (Chapter 27) resonates with Sarah’s journey (Chapter 25). Sonia’s introspection (Chapter 24) finds an answer in Kyendi’s mirror (Chapter 23). The book starts to feel less like a collection of letters and more like a single prayer spoken in 42 languages.

The book gets some things right and boosts strengths in certain areas. The metaphors land. Kintsugi. Cartography of the unseen. Writing as a war room. Writing as tango. These are not decorative — they are structural, holding the book together like gold in broken pottery.

The community dimension. This is not Izang’s book. It is a 43 people’s book. The WhatsApp fellowship, the secret editorial project, the daily Facebook posts that became ritual — all of this shows writing as fundamentally communal. You cannot become a writer alone. Jos knows this. The book proves it.

The Christian framework is not decorative or apologetic. For many of these writers — Micah (Chapter 3), Daniel (Chapter 5), Panshak (Chapter 32) — faith is the foundation of their craft. God writes first (on tablets, in sand, through prophets), and human writing is a response, imitation, participation in divine creation. Izang does not shy from this. He engages it fully, theologically, without condescension.

Practical wisdom for young writers. Wungakha’s five keys (Chapter 10): write frequently, read widely, be authentic, embrace criticism, and practice patience. Francis’s six realities (Chapter 17): vulnerability, accessibility, ease, reflection, courage, and accepting bad first drafts. These are not platitudes. They are distilled from lived experience.

However, there are some weaknesses in the book. Verbosity. Sometimes, Izang cannot resist showing you every book he has read, every philosopher who has touched the subject, every literary parallel. Chapter 12 drowns Omasirichi’s voice in the Enlightenment thinkers. Chapter 31’s rhetorical questions pile up until you forget what Ayinpo actually said.

Not enough challenge. The letters mostly affirm. Izang is generous, almost too generous. A more adversarial approach, where he pushes back on assumptions or interrogates contradictions, would have deepened the conversation. There are 42 letters here, but few arguments.

Repetition without variation. Healing. Becoming. Nobility. Community. These themes recur like liturgical responses, which is fitting, except liturgy knows when to stop. By the 30th letter, you have heard “writing as becoming” enough times that it starts to lose meaning.

The structure fights itself. Each letter is self-contained, which is beautiful. But it also means you get the same introduction-reflection-conclusion arc 42 times. The book would benefit from more formal experimentation, a letter written entirely in questions (Chapter 31 tries this), a letter that is pure dialogue, a letter that breaks its own rules.

There are some hard truths as well. Nenkangmun (Chapter 26) writes about rejection and gratitude as twins. She critiques the prosperity gospel tendency to “reject rejection,” insisting instead that rejection is inevitable and necessary. Growth does not come from avoiding failure; it comes from failing, learning, and failing better.

Izang responds by citing Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (rejected 28 times) and Chimamanda Adichie’s early manuscript (rejected so thoroughly she shelved it for years). Then he quotes Trevor Noah: Regret is worse than rejection. This is the book’s core insight: writing will break you. The question is whether you let the breaking destroy you or whether you repair yourself with gold.

Joseph(Chapter 8) was mourning his brother, killed in a banditry attack, when he wrote his letter on the poetics of writing. Rather than responding immediately, Izang postponed his reply, giving Joseph time and space to grieve. When he did return to it, he could have offered easy comfort. Instead, he honoured Joseph’s grief by taking his intellectual concerns seriously — engaging Aristotle, discussing Schopenhauer’s categories of writers, denouncing plagiarism as dross to be burned away in the refining fire. This is what fellowship looks like: not pretending the pain is not there, but building something meaningful alongside it.

Murakami’s writing style was influenced heavily by American literature and his deep love of jazz music, which shaped his focus on rhythm and natural flow over ornate language. His prose is notably simple and direct compared to the traditional Japanese literary style, creating work that translates exceptionally well across cultures.

Reading Letters to 42 Writers did something similar for me. I do not write poetry. I have said this before, and I admit it as a weakness. But this book, which is fundamentally about people finding their voices through writing, made me want to try. Made me think maybe voice is not something you are born with but something you build, line by line, failure by failure, until one day you look back and realise: Oh, there it is. That is mine.

The book would not teach you how to write a novel or a poem, or an essay. It would not give you plot structures or character arcs, or narrative techniques. What it would do — what it did for me — is remind you why writing matters. Why it is worth the broken sleep, the rejection letters, and the years of work that nobody sees.

Blessing (Chapter 41) calls writers “cartographers of the unseen.” We map territories that surveys cannot measure — grief, hope, becoming, the strange space between who we were and who we are trying to be. This is writing’s gift and its burden: to make visible what was hidden, to give language to what had none.

By Friday morning, making that pap at 4a.m., I understood why Izang spent 42 consecutive days writing these replies. Not because he had to, but because writing is how you pay attention, how you honor what people give you, and how you transform conversation into community into something that lasts.

If you are a young Nigerian writer, especially if you are from the North, where stereotypes suggest weakness in English expression, this book will be a mirror and a window. Sarah (Chapter 25) addresses this directly, rebuking generalisations while proving through her own journey that excellence comes from work, not geography. If you are part of any writing community — workshop, fellowship, online group — this book shows you what community can become when taken seriously. Not just a place to share drafts, but a space of genuine transformation.

Furthermore, if you are struggling with impostor syndrome (Chirka, Chapter 14; Shidobani, Chapter 40), or perfectionism (Angel, Chapter 20), or the fear that your disability disqualifies you (Nendirmwa, Chapter 21), you would find yourself in these pages. Not as case studies, but as people who walked through the same fires and came out refined. If you are curious about the intersection of faith and writing, the theological weight here, from Paul’s epistles to the tablets of Sinai to Jesus writing in sand, will give you language for something you might have felt but could not name.

And, if you are just tired. If you have been writing for years with nothing to show for it, except rejections, half-finished drafts, and the nagging sense that maybe you are fooling yourself, Lois (Chapter 28) will remind you that seeds can lie dormant for years before they bloom, that becoming is patient, and that the work you are doing now might not bear fruit until long after you hve stopped looking for it.

There is a passage in Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage where the protagonist realises his life has been shaped by an absence, something that happens years ago that he never fully process. The book’s entire plot is him going back, asking questions, and filling in the gaps.

That is what Letters to 42 Writers did for me. It filled in gaps I did not know were there. Made me realise I had been thinking about writing all wrong — as solitary work, individual achievement, personal expression. When, really, writing is what happens between people. In fellowship. In conversation. In the space where one person’s broken pottery meets another person’s gold.

I was supposed to be reviewing a novel. Instead, I spent a week with 43 strangers from Nigeria, learning what Jos has known all along: that craft matters, that community matters, that writing is the work of becoming human.

The cat showed up at my doorstep. I let it in. It is still here.