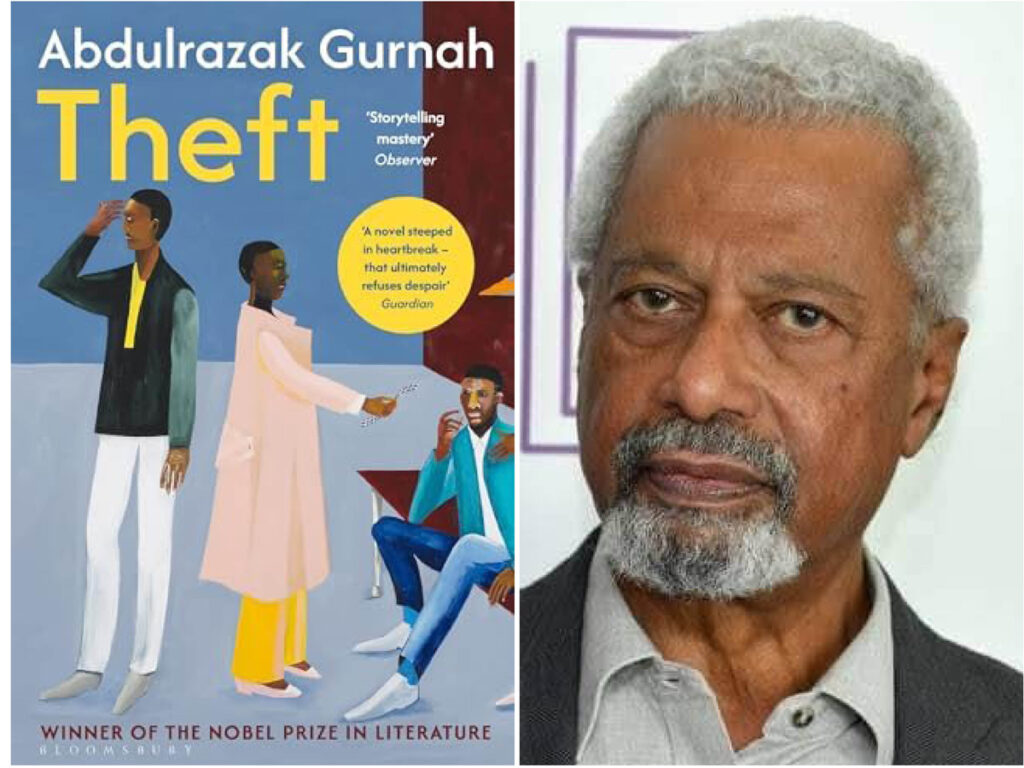

Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Theft is a novel that puts humanity itself on trial. Its narrative turns everyday events into moral witness statements. The book follows the lives of three characters — Karim, Badar, and Fauzia — as they move through postcolonial spaces shaped by power, inequality, and desire. Through these figures, Gurnah dramatises what is taken from people — not only property, but dignity, belonging, and love. Critics from the Financial Times and The Guardian have recognised Theft as one of Gurnah’s sharpest moral works, combining his usual calm storytelling with a biting question: what is truly stolen in modern life?

At the centre of Theft stand two contrasting lives. Karim and Badar are not simply men within a story; they are two verdicts of humanity. Karim, raised within a network of privilege and institutions, rises through the social ladder to become a respected government figure. His journey is marked by caution and conformity. He learns to speak the language of progress, success, and respectability. Yet, as The Guardian notes, “the tension between gratitude and subordination becomes central as Karim’s controlling nature strains his relationships.” This tension shows that his advancement depends on moral compromise. Karim’s life is a form of theft — he steals affection and authenticity from himself to maintain an image of success.

Badar’s story moves in the opposite direction. Introduced as a child servant, he carries abandonment and stigma from the start. “Your people did not want you,” he is told, a sentence that becomes both wound and prophecy. His exclusion defines his path, yet his response defines his soul. Unlike Karim, Badar’s triumph is inward. His life of endurance turns pain into clarity. Late in the novel, he reflects, “I have learned to endure.” That statement summarises the moral architecture of the novel — Gurnah’s belief that the last possession a human being must protect is the self.

The title Theft works on multiple levels. In an interview, Gurnah explained that “almost every character’s life is defined by that which is stolen from them by someone they once trusted.” The word “theft” thus extends beyond the act of taking things; it becomes a framework for moral analysis. Colonial structures, global tourism, and modern bureaucracy all serve as systems of theft. They take from local communities their dignity and agency, disguising exploitation as opportunity.

A passage from the Financial Times review captures this tension perfectly: the hotel’s rules warn workers, “Don’t make jokes and don’t laugh out loud. Don’t touch them!” These instructions are not only demeaning but reveal a theft of voice and humanity. The novel uses such details to show how structural hierarchies quietly colonize everyday life.

This social theft mirrors personal theft. Karim’s ambition robs him of intimacy, while Badar’s poverty threatens to steal his spirit. Between them, Gurnah stages a moral debate about what remains when everything visible is taken. Badar’s endurance is therefore a quiet act of resistance — a way of saying that not all thefts succeed.

Badar’s significance lies in his refusal to collapse into bitterness. His gentleness is his rebellion. Gurnah’s writing gives him an almost spiritual dimension; he embodies a form of ethical patience. This quality turns him into what critics have called “the moral heart of the book.” His endurance contrasts sharply with Karim’s pragmatic coldness.

If Karim represents the seduction of modern power, Badar represents its moral antidote. The two together form a parable: progress without compassion becomes another form of theft. Gurnah’s prose never preaches. He lets readers witness how choices unfold and what they cost.

This moral duality echoes the transcendentalist belief of Ralph Waldo Emerson that “to be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.” Badar achieves precisely this. He becomes himself fully, even within limits. His dignity cannot be stolen.

Similarly, William Ernest Henley’s words from Invictus illuminate Gurnah’s theme: “I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.” Badar’s life affirms this inward mastery. He loses almost everything material, but he never forfeits control of his moral compass.

Theft also acts as a study of social breakdown. Gurnah interlaces his critique of postcolonial inequality with the failures of family and community. Neglected children, absent fathers, and vulnerable women recur throughout the novel. Domestic spaces mirror national dysfunctions. A society that allows its families to fracture, Gurnah suggests, has already permitted a form of theft — the theft of care and responsibility.

The novel’s women, such as Aminah and Fauzia, carry this burden most visibly. Their constrained choices expose how gendered expectations operate as another form of expropriation. Love, work, and loyalty are negotiated under unequal terms. Yet within these structures, moments of kindness and honesty survive. It is through such quiet acts that Gurnah restores moral possibility to the reader’s view.

In Theft, Gurnah constructs what might be called moral theatre. Each character becomes both defendant and witness in the trial of humanity. Karim’s life warns of what happens when ambition outweighs empathy. Badar’s life demonstrates that moral strength is possible even within loss.

The verdict the novel offers is not cynical. Instead, it asserts that character survives theft. We can lose property, power, and belonging. These are real losses. Yet the true theft — the one that destroys — is the loss of obligation to others. Through Badar, Gurnah teaches that the greatest act of recovery is moral, not material.

Theft is not a loud book. It moves in quiet revelations. Its beauty lies in restraint. By the end, it holds a mirror to readers, asking whether we have also allowed ourselves to steal from others or from our own humanity. The lesson is enduring: to live ethically is to refuse the theft of compassion.

Badar, humble and wounded, embodies that refusal. His endurance restores meaning to survival. Karim, successful but hollow, illustrates its opposite. Between them, Gurnah maps the moral geography of our time.

Theft (literary fiction, 296 pages) by Abdulrazak Gurnah. Published in 2025 by Bloomsbury Publishing.

Izang Alexander Haruna is a poet and critic. He is the author of Letters to 42 Writers (2024) and the chapbook In a Man’s Body (2025). He is interested in a vast range of ideas, but with prime attention to African literature.