On a rainy Friday afternoon, inside one of the halls of BON Hotel, Ikeja GRA in Lagos, one of the panel sessions of the 13th edition of the three-day Ake Arts and Book Festival 2025 (theme ‘Reclaiming Truth’), which stretched beyond literature, was titled ‘Tunde Onakoya The Chess Champion’.

The panel was moderated by Kenyan-based cultural and literary advocate, Muthoni Muiruri, and featured chess master and founder of Chess in Slums Africa (CISA), Tunde Onakoya; writer and Ake Festival director, Lola Shoneyin; and graphic illustrator and architect, Kayode Onimole.

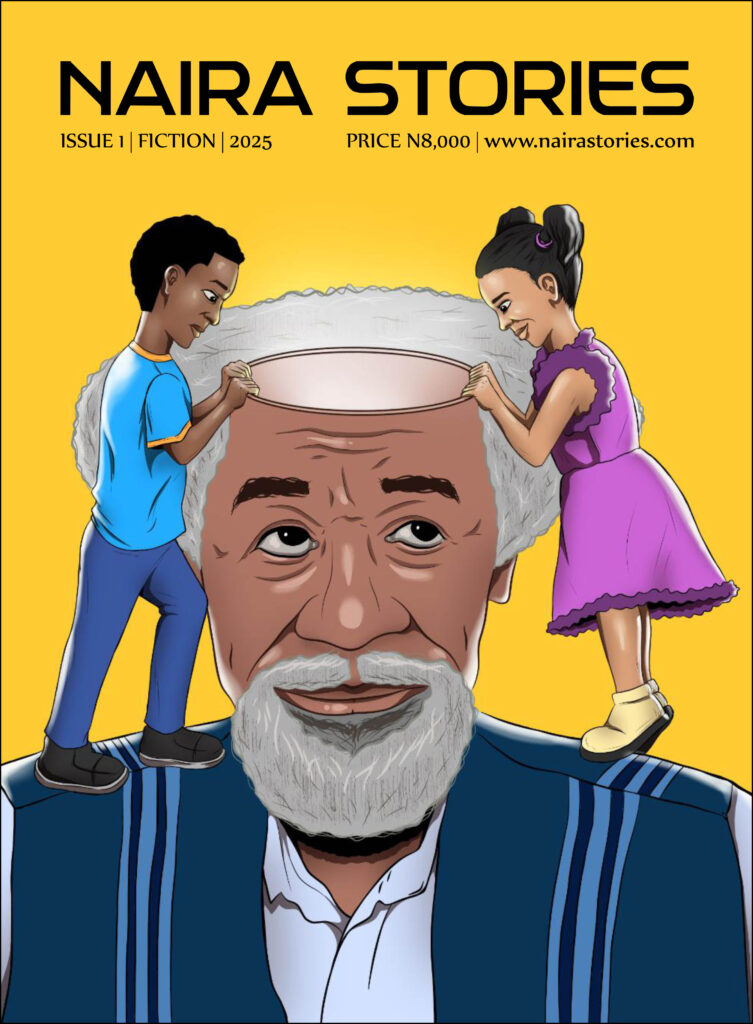

In the course of the interaction, what was expected to be a discussion on the book ‘Tunde Onakoya The Chess Champion’ — a children’s story book about the chess master written by Shoneyin with illustrations by Onimole — soon evolved into a profound reflection on memory, representation, childhood experience, and the children that society too often fails to see.

“We have been blessed with rain,” the moderator of the panel, Muiruri, said as she kick-started the panel. “So let’s be blessed with stories.”

These simple lines set the tone for an afternoon that would become one of the most memorable sessions of the festival.

Tunde Onakoya, now celebrated globally for transforming underprivileged children through chess, surprised the audience by taking them back to a version of himself that a few had ever imagined.

At age ten, he could hardly read or write. His world was defined by survival, not imagination. Yet, life shifted the day he stumbled across two books, ‘Step-by-Step Chess’ and ‘Gulliver’s Travels’. These titles, gifted almost by chance, opened a portal out of poverty and into possibility for the chess master.

“Reading that book was a very important reflection point for me,” he said. “It introduced me to a world that existed beyond the one I grew up in.”

It was a quiet reminder that sometimes, the most limited access can unlock the greatest potential.

Illustrator Kayode brought a different kind of magic to the conversation, the craft of giving a story a face, and giving children someone they can visually root for. But illustrating a childhood that the world had never seen was not simple.

He explained how he studied Lola’s reference images, zoomed in on old photos, and used Shape Theory to create young Tunde’s facial structure.

“His head is a square,” he joked. “His jaw is a square, and that’s what I used all through.”

The hall erupted in laughter, but beneath the humour was intention. Kayode was not just creating art — he was building dignity into every line and contour. To illustrate a child correctly is to honour his story, and Kayode understood the weight of that responsibility.

For the author of the book, Lola Shoneyin, representation is not an abstract academic idea; it is a lived experience. She told the audience about being a six-year-old Black girl in a Scottish boarding school, where she felt out of place, invisible, and aching for a world that looked like her.

Years later, the moment that changed her came in a classroom in Kaduna. She was reading to children who had rarely, if ever, seen characters that resembled them. But the energy in the room shifted instantly when she showed the children images that looked like them in the book she wrote for one of her children.

“They leaned in the moment they saw faces like theirs,” she said. “That was when I understood what representation really means.”

Her Northern Lights Series, now eight books strong, was born from this revelation. “Children need their own heroes. And I knew Tunde’s story was one they needed now,” she said.

When Shoneyin first approached Onakoya about turning his childhood experiences into a book, he rejected the idea — not out of fear or reluctance, but because he felt his story was still unfolding.

“I didn’t think I had finished becoming,” he shared.

But Shoneyin reframed everything. A story did not have to be told at the end of a journey. It could be documented in chapters, each one holding its own value. That conversation unlocked the possibility for the book, and Onakoya revisited memories he had long buried.

The result is a story powerful enough to carry children from the chaos of slums in Lagos and other parts of Nigeria to the bright lights of the Times Square in New York in the United States, a testimony of grit, determination, and hope.

One of the most emotional moments of the afternoon came when Onakoya shared the story of taking five children, all from some of the toughest communities in Lagos, to New York.

In Times Square, crowds gathered to watch the children play chess. People clapped. Strangers asked for photos. The same children who were often ignored or dismissed back home were suddenly celebrated.

“People finally saw them,” he said softly. “A couple of years ago, no one even knew their names.”

The room fell silent. It was a reminder of how transformative visibility can be for a child who has lived their entire life unseen.

During the question and answer (Q&A) session, a young woman asked a question that resonated deeply with Lagosians. “What do you do,” she asked, “when street children become violent? Where do you draw the line?”

It was an honest question, one born not from judgment, but from fear and confusion. Onakoya paused before answering. When he finally spoke, his voice carried the weight of years spent working with children the world calls “Area Boys.”

“A child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth,” he answered.

He explained the ecosystem of survival that pushes children into violence, abandoned homes, poverty, gangs, manipulation, and trauma. He emphasised that people often mistake symptoms for identity.

“It’s not that the stories of violence are untrue,” he said. “They are just incomplete.”

Then he told the story of Yusuf, the 13-year-old who recognised him at a mall even though they had never spoken. The boy remembered a line from one of Onakoya’s chess classes in Lagos organised for young people.

“Chess players,” the boy said.

“Observe,” Tunde replied.

It was a short exchange, yet a reminder that dignity, when offered, is never forgotten.

Onakoya closed his response by drawing a subtle but necessary distinction. People should protect themselves. No one should put themselves in danger. But even in moments of fear, he urged the audience never to lose sight of the child behind the behaviour.

“If the first story you tell yourself about a child is anger, then you’re not seeing that child at all,” he said.

The true crisis, he explained, is not the boys tapping on car windows. It is the society that abandoned them long before they reached the street.

As the session ended and the rain outside softened into a quiet drizzle, the hall remained filled with a lingering electricity. People stayed back, discussing, reflecting, absorbing the depth of what had just been shared. It became clear that this was more than a literary conversation. It was a call to action, a reminder that storytelling is one of the most powerful forms of social change.

Stories matter. Representation matters. Seeing children, truly seeing them, matters. Because a child who is seen grows into an adult who shines. And on this rainy Lagos afternoon, three storytellers helped a room full of people see children a little more clearly.