On November 10th, 2025, my team and I were supposed to present to our company’s leadership — after fourteen months of working there, after three months on this specific project, after 24 pages of PowerPoint slides I had rehearsed until I could recite them in my sleep. I was second in line. I never made it past the opening.

One of our leads stopped us mid-presentation. The superior complex was palpable. We had not done justice to the project, they said. Come back in three months. Start fresh. I had prepared for days and nights. The work was there. The research was solid. But someone decided it was not the right time, was not quite ready, and needed postponement.

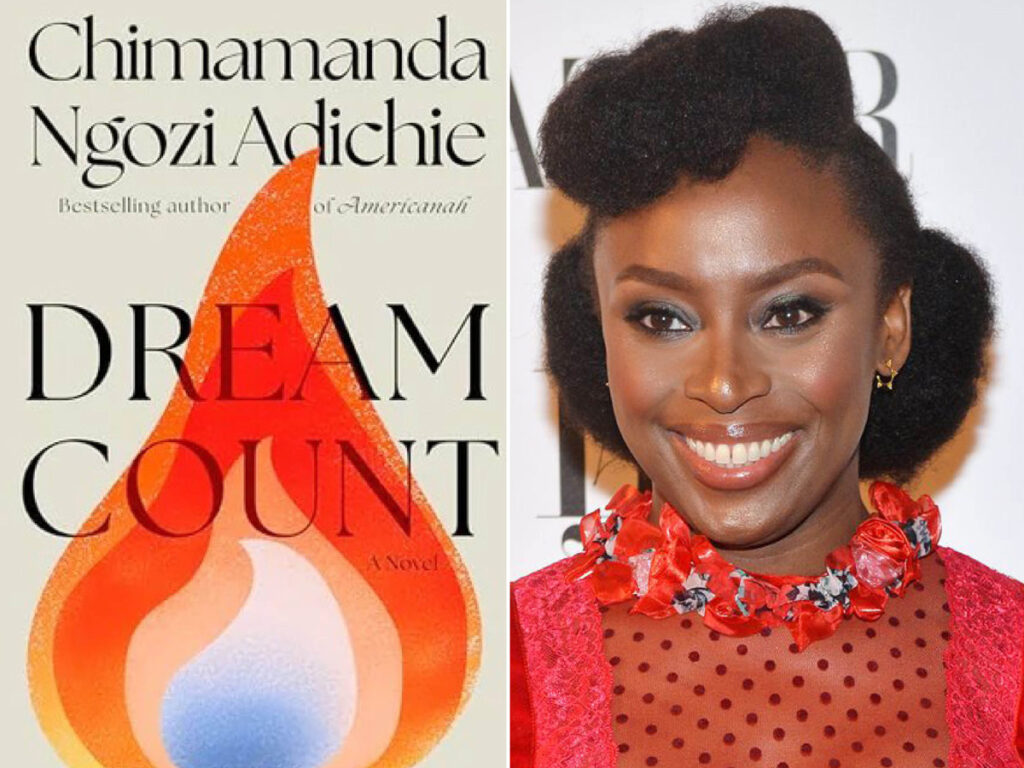

I thought about that delay — that particular species of disappointment — whilst reading Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dream Count. In Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood, the narrator observes: “If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.” But what happens when everyone reads the same novel for different reasons?

Dream Count arrives twelve years after Americanah, and that gap matters. In those twelve years, Nigerian literature transformed. Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀’s Stay With Me (2017) explored marriage and infertility with surgical precision. Lesley Nneka Arimah’s What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky (2017) won the Kirkus Prize for stories that bent reality whilst staying rooted in Nigerian women’s lives. Akwaeke Emezi pushed boundaries of gender and identity. Oyinkan Braithwaite showed Nigerian fiction could be swift, dark, and strange. Oyin Olugbile’s Sanya (2025) won the Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas (NLNG)-sponsored Nigeria Prize for Literature for boldly reimagining Yoruba mythology, casting Sango as female.

These writers learned from Adichie’s path, then walked their own. They compressed where she expanded. They trusted silence, where she explained.

Dream Count reads as though Adichie did not notice.

“I have longed to be known, truly known,” Chiamaka begins on page one. It is a beautiful sentence. The kind that should land like a stone in still water, sending ripples outward.

Instead, Adichie revisits this yearning — through Chiamaka’s relationships with Darnell, with Chuka, with the married Englishman, with Johan, with Luuk, with men whose names blur together — until it becomes white noise. The same emotional beats circling back. The same realisations reached and then forgotten. The same men disappointing in identical ways.

When Adichie writes, “I wanted love, old-fashioned love. I wanted my dreams to float with his,” there is genuine ache. Or when Chiamaka confesses: “I was content, sated. I was where I was supposed to be. Yet in quiet moments, alone, I feared that my contentment was a kind of resignation” — this precision reminds you why we waited twelve years.

But these moments are scattered like good china in a house of empty rooms.

Murakami’s characters show us loneliness through action. They cook elaborate meals at 3a.m., organise record collections, iron shirts with ritualistic care. In Dream Count, the women mostly think about their solitude, analyse it with a surgeon’s precision, but we rarely see them being alone.

The closest we come is through small, specific details: the deer in Chiamaka’s Maryland garden during lockdown. Toilet paper queues. A spoon someone left at an ATM. These details — mundane, unremarkable — are where the novel breathes. They are the kind of thing Murakami notices: the exact temperature of water for tea, the way light falls at 4p.m.

But Adichie does not trust them to carry weight. She explains everything, as though afraid we would not understand. In her earlier work, she trusted readers more. Half of a Yellow Sun did not explain the Biafran War’s horrors; it showed you a bowl of garri and let you understand hunger. Purple Hibiscus did not psychoanalyse Eugene; it showed you a kettle of boiling water and let you understand fear.

Dream Count has forgotten this trust.

Let me be direct about the Nafissatou problem. In 2011, Nafissatou Diallo, a Guinean hotel housekeeper in New York, accused Dominique Strauss-Kahn of sexual assault. The case collapsed. She settled. She gave interviews. She wrote a book. She asked to move on.

In 2025, Adichie brings her back — spanning over 100 pages of the novel. Adichie writes in her author’s note that she wanted to give Nafissatou an alternative ending, one in which dropping the case brings relief rather than defeat. The fictional Nafissatou does find relief when the charges are dropped. She is exhausted, not devastated.

But here is what troubles me: the real Nafissatou Diallo already had her ending. She already told her story on her own terms. What Adichie offers is not rescue; it is replacement. Her imagination of what Nafissatou should have felt, standing in for what Nafissatou actually did feel.

The novel renders Nafissatou with what one reviewer calls “ethnographic distance” — explanations of female circumcision, mining conditions, and West African migration patterns. We see Chiamaka from the inside: her every thought, every doubt. We see Nafissatou from the outside: her circumstances, her suffering, but never quite her.

There is something uncomfortable about a wealthy, celebrated Nigerian author fictionalising the trauma of a working-class West African migrant for an international audience. The class distance shows.

Omelogor should be the novel’s most intriguing character. She is successful, unmarried, unapologetic — a Lagos banker who has made her money and her life on her terms. Instead, she becomes a mouthpiece. Pages and pages of monologues about American progressives, cancel culture, performative wokeness. Lines like: “They were ironic about liking what they liked for fear of liking what they were not supposed to like.”

It is not wrong, exactly. There is truth in her observations about the provincialism of American moral certainty. But it reads less like character and more like author — Adichie working through her own grievances with her critics, her fury at being misunderstood.

One Nigerian reviewer captures it precisely: “Chimamanda ultimately deploys Omelogor as a weapon against the people who have disagreed with her so much over the years.”

Murakami’s most political work, 1Q84, embeds its critique of religious cults and authoritarianism within a love story and a mystery. You can read it without noticing the politics. You cannot experience Omelogor’s sections without feeling lectured.

Zikora’s story is the shortest. She wants marriage, motherhood, and the traditional life. She is abandoned whilst pregnant by Dr Kwame. She gives birth in agony. She discovers her mother’s hidden strength. The childbirth scenes are visceral, unsentimental, real: “You don’t know how bristly sanitary pads are until…” The mother’s revelation — “There were no miscarriages” — reframes an entire relationship in one sentence.

These moments show Adichie can still do this: can render the body in pain, can deliver revelation through restraint rather than explanation. But Zikora herself remains underwritten. She is more symbol than self, more idea than person.

There is a Yoruba saying: “Kò sí ẹni tí ó lè wo inú ọmọ ẹlòmíràn” — No one can see inside another person’s heart. But novels try. That is their purpose: to let us peer inside hearts not our own.

Dream Count succeeds when it stops explaining and simply shows: “She felt hemmed in by shame, a shame forced upon the innocent, glowing in unfairness. She had done nothing wrong; it was she who had been harmed, and yet she felt shame as an acute rupture of her internal order.”

Or: “Foreigners go on and on about the challenges of emerging markets, not knowing that the biggest is the hubris of irresponsible men.”

Or: “Nothing beats living in your own country if you can afford the life you want.”

These are the moments that remind me why we waited. But they are too few, and the spaces between them are filled with explanation, repetition, and digression.

An Australian reviewer writes: “I was bored by the witterings of three middle-aged super-wealthy women about their unsatisfactory love lives with uniformly unsatisfactory men.”

It is harsh, but there is truth in the exhaustion. These are privileged women with privileged problems — which is fine. Many great novels follow the well-off. But privilege requires precision. You must show us why we should care about these particular wealthy women’s particular wealthy problems.

Adichie almost gets there. She shows how Chiamaka’s privilege does not protect her from racism, how Omelogor’s money cannot fill the hole left by her uncle’s murder, how Zikora’s law degree means nothing when she is bleeding and alone. But she explains it all so thoroughly that the showing gets buried under the telling.

The Wall Street Journal notes: “The four women are sympathetic allies, but they tend to be better at diagnosing each other’s problems than facing their own.”

This is the novel’s truest insight, and perhaps its most damning self-critique. These women know things. They analyse, perceive, and understand. They can tell you exactly what is wrong with everyone around them. But knowing does not save them. Understanding does not transform them. They end roughly where they began: aware but unchanged.

Chiamaka still yearns to be known. Zikora still measures herself against impossible standards. Omelogor still rages at the world from her beautiful house. Nafissatou still carries shame that is not hers to carry.

In Murakami’s work, this stasis would be the point: the acknowledgement that some loneliness is permanent, some wounds do not heal. But Adichie’s narrative does not quite commit to this bleakness. It hovers between resignation and hope, unable to settle on either.

Here is what Dream Count gets absolutely right: the specific texture of diaspora consciousness during COVID-19.

The Zoom calls with family in Nigeria, where you can see your mother’s face but not touch her hand. The code-switching that happens automatically, your voice changing registers depending on who is listening. The way Lagos and Maryland exist simultaneously in your mind, neither quite home, both impossible to leave.

When Adichie writes about Chiamaka watching pandemic news from America, there is a particular vertigo she captures: the guilt of safety, the helplessness of distance, the way crisis reveals which version of yourself you have become. This is hard to write well, and Adichie does it with precision. But one strong pillar does not hold up a house.

A Nigerian reviewer asks the question that haunts this book: “If it were not Chimamanda that wrote Dream Count, would you think it was good?”

I keep asking myself the reverse: If this were a debut by an unknown writer, what would I say? I would say: This author has technical skill and genuine intelligence. The prose is controlled, occasionally beautiful. But the structure needs tightening: cut 100 pages, especially the Nafissatou section, which feels like a different book entirely. Trust your readers more. Do not explain every emotion. Give us one narrator instead of four, or find a stronger thread connecting them.

I would say: This writer has promise. Come back when you have lived with these characters longer, when you know them well enough to let them surprise you. But it is not a debut. It is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who has already written the books we needed. This makes this work not promising but bewildering.

My presentation that never was. That is what keeps coming back to me. The work was done. The slides were ready. I had prepared the arguments, anticipated the questions, and rehearsed until the words felt natural. But someone decided it was not time yet. Not good enough yet. Come back later. Start fresh.

That is what Dream Count feels like: a presentation that got postponed. Not because the work is not there, but because something fundamental is misaligned. The timing is off. The audience has changed. What would have landed twelve years ago does not land the same way now. Adichie has written a tale about women yearning to be known, but she has not trusted us — her readers — to know these women without constant guidance. She has written about disappointment without fully inhabiting it. She has written about change whilst her characters remain essentially unchanged.

The Australian reviewer concludes: “Dream Count is ordinary.” That is the word that cuts deepest. Not bad. Not failed. Ordinary.

From any other author, ordinary would be fine. From Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie — who gave us Kambili’s silence, who gave us Ifemelu’s blog posts, who showed us how to render Nigeria for the world without translating it — ordinary is heartbreaking.

Three months from now, my team will present again. We will revise, tighten, and prepare differently. Maybe it will land better. Maybe the timing will be right. Maybe we will get past the second slide. Or maybe we will realise the problem was not the presentation at all: it was what we were trying to present. That the fundamental conception needed rethinking, not just revision.

I suspect Dream Count is the latter. No amount of editing would have fixed what is essentially a crisis of form and purpose. This is a work that needed to be three different books, or perhaps one much shorter, tighter volume about Chiamaka alone. Instead, it is a compromise: attempting to satisfy too many demands at once — the personal essay, the social critique, the immigrant narrative, the pandemic chronicle, the defence against critics. All of these impulses are legitimate, but together they sprawl and contradict rather than cohere.

P.S.: I read the novel in full. I have referenced three published reviews that helped clarify my thinking (from anzlitlovers.com, Medium, and The Guardian). All specific textual references come from my own reading or from these verified critical sources. No details have been fabricated.