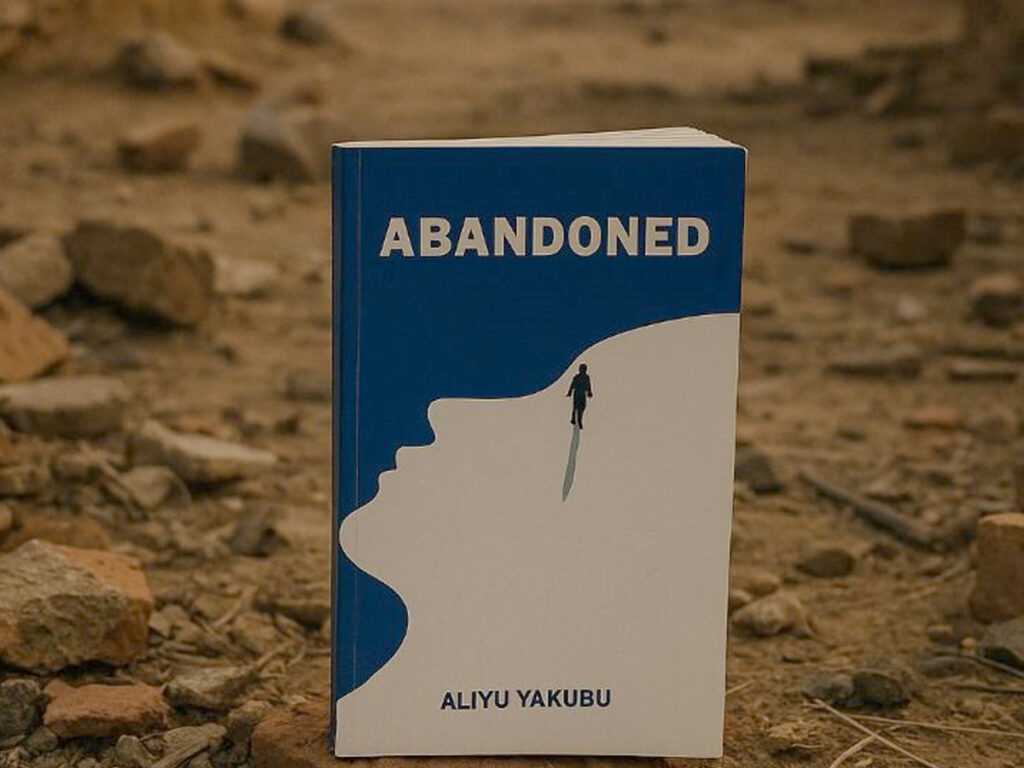

The orange cat arrived on the same Wednesday as Aliyu Yakubu’s Abandoned. Every morning, at seven, it sits by my compound’s gate, waiting for what? Food, shelter, and someone who will never return. Yesterday, I wondered if it had read these stories, because it understands something most of us forget — that what you are waiting for has already decided not to come back.

This is Yakubu’s territory. Across ten stories, he maps the psychology of abandonment in a Nigeria where systems fail with such routine precision that catastrophe becomes an ambient condition. Reading his collection whilst NEPA’s light flickers puts you in the right frame of mind — not for Nollywood drama, but for the quiet mathematics of institutional collapse, the arithmetic by which people calculate what they must sacrifice to keep breathing.

‘Knock on the Gate’ opens like an Afrobeat track you recognise until the rhythm shifts. Dr Abdul hears the knock, sees the stranger searching for his brother, and despite Fa’iza’s intuition — which operates on frequencies most men have learnt to ignore — he opens the gate. The robbery that follows feels inevitable because we know Nigeria’s cruel equation: kindness gets you robbed. This is not cynicism; it is accounting.

Yakubu suggests that hospitality in our culture is not mere kindness but prayer. We feed strangers, hoping someone feeds our own when they wander lost. But prayer, like compound gates, works both ways. Sometimes, what you invite in is not a blessing but a reckoning.

The collection’s genius lies in its refusal to pathologise poverty. Yakubu excavates something deeper: how systematic abandonment restructures consciousness itself.

In ‘The Bawdy House’, Bappa’s descent from vegetable seller to gambler follows tragedy’s true timeline — gradually, then suddenly, then completely. When he sits in his makeshift room, counting money that is not there, I thought of an Abuja taxi driver who once told me: “Money is like respect. You don’t notice it until it’s gone, then you notice nothing else.”

This is literature as a witness to what happens when societies abandon their vulnerable, not documentation but archaeological excavation of damaged psyches.

Consider ‘Deflated Balloon of Empathy’, the collection’s most perfect title. The head nurse at Shehu’s clinic — a woman whose compassion has been punctured by patients who vanish after treatment — embodies Nigeria’s peculiar tragedy: caught between Hippocratic duty and capitalist necessity, between Christian charity and survival arithmetic. Her empathy deflates not because she stops caring, but because caring without boundaries becomes suicide.

The title story delivers its blow with surgical precision. Danliti’s mother drugs him at a Kaduna motor park before disappearing, not from cruelty but from logic so brutal it approaches compassion. Her freedom requires his abandonment. What follows — his rejection by almajiris, night on cold pavement, absorption into Gidan Gwaska’s criminal den — maps complete institutional failure. Every safety net has holes. Every system designed to catch the falling has learnt to look away.

Yakubu refuses easy blame. Who is responsible? Mother? Absent father? The almajiri system? Economic structures that create such choices? The question becomes meaningless. The machine is too large, its gears too numerous, its operation too systematic for individual accountability.

‘Stolen Innocence’ compresses a novella’s symphonic complexity into short story form. Misbahu’s journey from village boy to an accomplice traces not just corruption but an ecosystem collapse. The almajiri system, designed for religious education and social mobility, becomes instead a pipeline for exploitation. Kaura, grooming children for crime, is not a monster but an entrepreneur responding to market conditions. The market happens to be in children.

When Misbahu betrays Salimah, a woman who showed him kindness, the tragedy lies in his absence of alternatives. He has been trained to see relationships as transactions, kindness as weakness, trust as opportunity. The judge calls him a victim rather than a criminal, but the distinction feels crucial and inadequate simultaneously. Victimhood does not resurrect trust.

Contemporary Nigeria stalks these pages. In ‘Is She Doing Drugs?’ Fadilah returns from university exhibiting depression, but her family cycles through familiar diagnoses: spiritual attack, drug abuse, waywardness. Yakubu’s genius is showing how diagnostic confusion becomes another abandonment form. Fadilah disappears into her own mind whilst those who love her argue whether her suffering is medical or spiritual. The gap between explanations swallows people whole.

‘Redemption’ poses the collection’s most complex moral equation. When Hindatu’s abusive husband dies in a car accident, her smile contains multitudes — grief, relief, guilt, hope. Can death be mercy? Can an accident be providence? Yakubu refuses answers, offering instead recognition that moral complexity increases under pressure.

‘Gordian Knot’ examines widowhood as social death. Ladalo’s husband’s family seizes property whilst the community transforms from supportive to suspicious. The biblical verses that sustain her become both refuge and irony, divine comfort against human cruelty. When her family finally intervenes to restore dignity, the resolution feels less like justice than accident, random kindness occasionally interrupting systematic abandonment.

Reading this collection during Nigeria’s current economic challenges adds unintended layers. The naira’s instability, fuel price fluctuation, and the sense that institutions are failing or have failed. These realities make Yakubu’s stories feel prophetic rather than descriptive. These are not poverty narratives — they are psychological studies of living in systems designed to produce surplus people.

What distinguishes Abandoned from other social realism is its psychological subtlety. Yakubu does not document how poverty affects behavior. Rather, he excavates how it restructures consciousness, transforming the very categories through which people understand possibility, morality, and relationships. His characters do not merely react to circumstances; they internalise them, becoming accomplices in their own diminishment.

The collection’s few weak stories explain when they should suggest, conclude when they should linger, moralise when they should observe. But these are complaints recognising exceptional talent and wanting more. Yakubu writes with lived authority — his Nigeria neither romanticised nor condemned but simply witnessed, where good people make terrible choices and terrible people occasionally surprise themselves with grace.

Fela Kuti once said the most important musical element is not what you play but what you leave out — spaces between notes that create meaning. Yakubu understands this principle. His stories gain power from silence: Danliti’s mother’s guilt, the stranger’s humanity in ‘Knock on the Gate’, redemption possibilities hovering just beyond reach.

In an era when Nigerian writing increasingly looks outward for validation, Yakubu has written inward, excavating psychological and social realities with archaeological patience and surgical precision. This is art as accounting for what societies lose when they abandon their most vulnerable — storytelling that matters because it refuses comfortable distance from suffering’s mathematics, empathy’s economics, the brutal calculus determining what people can afford to lose.

The cat is still by the gate this Thursday evening as the Maghrib prayer drifts across Lagos and generators cough to life in the distance. It found a cardboard box for shelter. Small mercies. Outside my window, the city continues its ancient survival business — impossible choices, unexpected kindness, abandoning what cannot be carried, carrying what cannot be abandoned.

Abandoned reminds us that every story contains two narratives: what happens and what it costs. In our age of easy answers, Yakubu offers something rarer — a difficult truth that most life occurs in grey spaces between right and wrong, where abandoned children become criminals, abandoned wives find freedom in widowhood, and abandoned societies produce stories like these: beautiful in honesty, terrible in accuracy, essential in ways only literature can be.