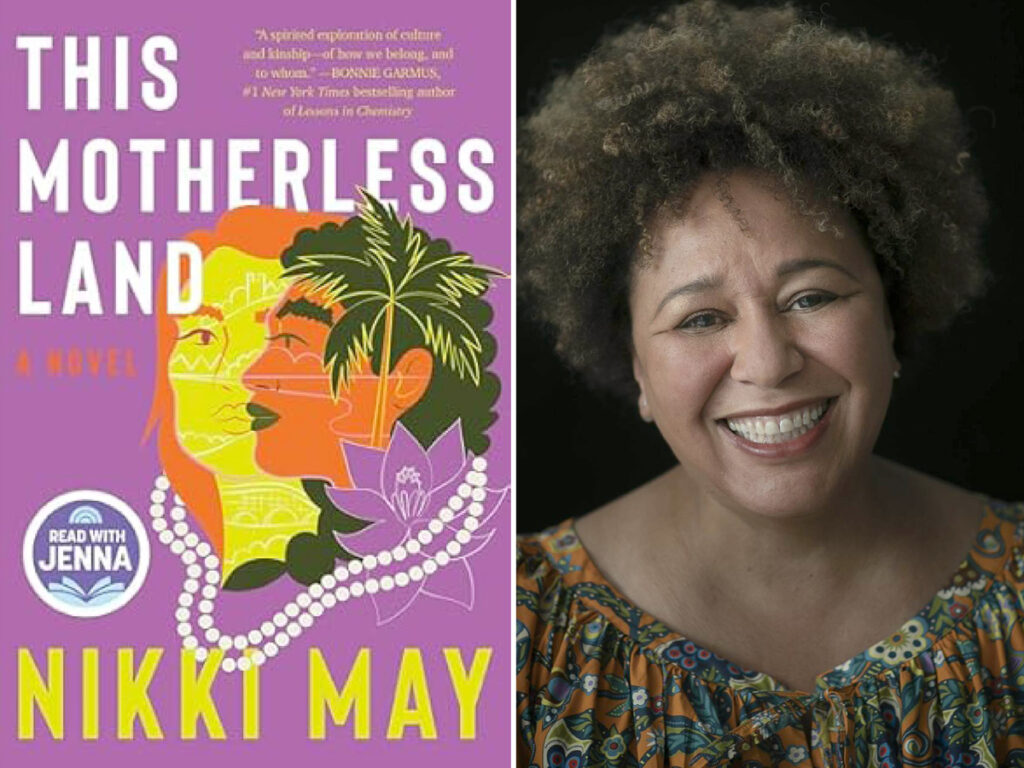

Last Sunday evening, I closed Nikki May’s This Motherless Land with the peculiar feeling that I had just witnessed something between a family autopsy and a resurrection ceremony. There was that quality you find in certain Lagos afternoons when the harmattan dust settles and you can suddenly see clear to Victoria Island — except what became visible was not skyline but the intricate machinery of how families destroy themselves across continents and generations.

The book had demanded everything — patience through its occasionally meandering middle sections, anger at its unflinching portrayal of institutional cruelty, and ultimately, a kind of exhausted hope that felt earned rather than gifted, like finding a twenty-naira note in an old agbada pocket.

May’s narrative operates as both intimate family drama and systemic critique, employing what might be termed a “bifocal narrative structure” that forces readers to simultaneously inhabit two consciousnesses shaped by the same foundational trauma. The novel’s central achievement lies not in its exploration of familiar themes — racism, displacement, family toxicity — but in its rigorous examination of how these forces reproduce themselves across generations and continents through the mechanics of institutional power and psychological conditioning.

May’s narrative architecture deliberately evokes with American sociologist and civil rights activist, W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963), describes in his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk as double consciousness, while extending it beyond racial identity to encompass what we might call “spatial consciousness”, the psychological fragmentation that occurs when belonging is perpetually deferred across geographic and cultural boundaries.

Funke’s transformation into “Katherine” functions as more than cultural assimilation; it represents what Indian-British postcolonial theorist Homi K. Bhabha, in his 1994 book titled The Location of Culture, describes as colonial mimicry, where the colonised subject must approximate the coloniser’s identity while remaining forever marked as imitation.

The novel’s genius lies in its demonstration that this spatial consciousness operates bidirectionally. Liv’s eventual journey to Lagos reveals her own fractured relationship to place and identity, suggesting that privilege itself creates a form of displacement, what we might term “inherited rootlessness” passed down through generations of imperial wealth extraction.

May employs alternating perspectives not merely for dramatic tension but as a formal embodiment of the novel’s central theme: the impossibility of singular narrative truth under conditions of systemic oppression. The bifocal structure mirrors the characters’ fractured consciousness while forcing readers to experience the cognitive dissonance of simultaneous belonging and exile.

The temporal architecture deserves particular attention. By opening in 1978 Lagos before cutting to 1980s England, May establishes what French literary theorist, Gerard Genette (1930-2018), in his 1980 book Narrative Discourse, conceptualised as Analepsis (flashback) and prolepsis (flash-forward), narrative techniques that manipulate time, showing that the idyllic past exists primarily to illuminate the violence of its destruction. This temporal manipulation serves an ideological purpose: it demonstrates how trauma reorders memory, making the past simultaneously precious and inaccessible.

The novel’s most sophisticated technical achievement is its handling of linguistic register. Funke’s code-switching between Nigerian pidgin, Yoruba, and received English pronunciation functions as more than characterisation; it embodies the psychological labour required to maintain multiple identities simultaneously. When May writes Funke’s interior monologue in medical terminology while rendering her speech in Nigerian vernacular, she reveals the exhausting performance of professional respectability that constitutes a survival strategy rather than an authentic expression.

May’s analysis of racism operates with sociological precision, avoiding both liberal individualism (racism as personal prejudice) and structural determinism (racism as unchangeable system). Instead, she demonstrates how racial hierarchies reproduce themselves through apparently neutral institutions — legal systems, educational structures, family inheritance — that function as what French Marxist philosopher, Louis Althusser (1918-1990), in his 1971 book Lenin and Philosophy, would term “ideological state apparatuses.”

The deportation sequence exemplifies this analysis. Funke’s removal from England occurs not through spectacular violence but through bureaucratic efficiency: false accusations, manipulated evidence, institutional complicity. The police chief’s casual cooperation with Margot reveals how power networks protect themselves through selective law enforcement, while the framing of Funke for theft and drug possession demonstrates how criminalisation functions as a racial management strategy.

Crucially, May extends this analysis to examine how oppression operates within oppressed communities. Funke’s grandmother’s rejection based on àjẹ́ pupa beliefs illustrates what Martinican psychiatrist and revolutionary, Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), in his 1952 book Black Skin, White Masks, identified as internalised oppression — how colonised people adopt the coloniser’s negative views of themselves or, better still, the deployment of traditional cultural frameworks against community members in ways that ultimately serve colonial interests. The grandmother’s superstition, while culturally authentic, functions as a mechanism for maintaining female subjugation within patriarchal structures.

May navigates the treacherous terrain of cultural representation with remarkable sophistication, avoiding both orientalist exoticism and defensive cultural nationalism. Her Lagos is neither a romanticised homeland nor a dystopian warning. It emerges as a complex urban space containing multiple contradictions: Professor Soyege’s intellectual snobbery alongside Oyinkan’s generous friendship, traditional misogyny coexisting with women’s professional achievement.

The novel’s treatment of Funke’s medical career provides particularly astute social commentary. Her navigation of sexism in Nigerian medical education — the sexual harassment, professional undermining, expectations of gratitude — demonstrates how patriarchal structures adapt across cultural contexts while maintaining essential functions. May refuses to position Nigerian sexism as either more or less problematic than English racism. Instead, she reveals how both operate as variations of the same fundamental logic: the systematic exclusion of certain bodies from full human recognition.

The Yoruba proverb “Eniyan l’aso mi” (“people are my covering”) that Funke adopts as personal philosophy functions as more than a cultural authenticity marker. It represents an ideological positioning that prioritises community relationships over individual accumulation. This stands in direct opposition to the inheritance-driven logic that structures English family dynamics, suggesting alternative value systems rather than simply lamenting cultural loss.

The novel’s exploration of intergenerational trauma operates with psychoanalytic sophistication that extends beyond individual psychology to examine how collective historical wounds reproduce themselves through family structures. Margot’s cruelty toward Funke emerges not as a personal choice but as a symptomatic expression of deeper imperial anxieties about racial mixing and cultural contamination.

The bottle-top talisman functions as what French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) calls objet petit a, a concept where objects represent unconscious desire or trauma, simultaneously revealing and concealing psychological truth. Funke’s self-harm with this token reveals her unconscious understanding that survival requires carrying pain physically rather than processing it psychologically. The bottle-top’s transformation from childhood game to self-injury instrument to protective charm traces the novel’s broader arc from innocence through trauma to provisional healing.

Liv’s drug addiction similarly operates as a symptomatic expression of inherited guilt. Her cocaine use represents an attempt to escape the unbearable knowledge of her complicity in Funke’s destruction while simultaneously punishing herself for that complicity. The addiction’s repetitive structure mirrors the compulsive nature of trauma repetition, suggesting that healing requires breaking cycles rather than simply acknowledging harm.

This Motherless Land contributes significantly to contemporary literary examinations of displacement and diaspora experience, but distinguishes itself through its focus on intra-imperial rather than postcolonial migration. Unlike novels such as Zadie Smith’s White Teeth or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, which primarily examine movement from periphery to centre, May explores circulation within imperial networks where power relations remain asymmetrical despite geographical mobility.

The novel’s most original contribution lies in its analysis of what we might call “imperial kinship” — family structures that span colonial territories while maintaining hierarchical relationships embedded in those territories’ historical power dynamics. The Stone family’s treatment of Funke reveals how domestic intimacy does not provide protection from racial violence. Indeed, the family structure itself becomes a vehicle for reproducing colonial relationships at an intimate scale.

Despite its considerable achievements, the novel contains structural weaknesses that prevent it from reaching absolute critical heights. The most significant concerns are pacing and resolution. May constructs psychological complexity with admirable patience across three parts, then attempts to resolve decades of trauma through compressed final sections that prioritise narrative closure over psychological realism.

The inheritance revelation, while thematically appropriate, arrives too late to function as more than a plot device. Had May introduced this element earlier, perhaps as rumour or partial knowledge, it could have provided additional psychological tension throughout Funke’s development rather than serving primarily as a deus ex machina for final reconciliation.

Character development suffers from similar telescoping. Margot remains frustratingly one-dimensional despite her central importance to the novel’s ideological critique. While her consistency serves thematic purposes, demonstrating how racism operates through ordinary people rather than exceptional monsters, it limits the novel’s psychological complexity. A single scene revealing her vulnerability or uncertainty could have provided depth without undermining her function as antagonist.

The novel’s treatment of healing and reconciliation, while emotionally satisfying, lacks the psychological complexity that characterises its exploration of trauma. Funke and Liv’s reunion, though moving, compresses too much emotional processing into too brief a timeframe. May seems more committed to providing therapeutic closure than examining the difficult, non-linear process of trauma recovery.

This Motherless Land succeeds most powerfully as a cultural intervention, insisting on the complexity of Nigerian experience while refusing to perform that complexity for Western consumption. May’s confidence in cultural specificity — the untranslated Yoruba phrases, the detailed Lagos geography, the assumption of reader familiarity with Nigerian social dynamics — functions as quiet literary resistance to demands for cultural translation.

The novel’s exploration of class dynamics within Nigerian society provides a particularly valuable contribution to contemporary African literary discourse. The tensions between diaspora returnee privilege and local authenticity, the hierarchies that reproduce colonial structures within postcolonial societies, the ways that foreign education simultaneously empowers and alienates — these themes receive sophisticated treatment that avoids both romantic nationalism and neocolonial pessimism.

This Motherless Land establishes Nikki May as a significant voice in contemporary fiction through its rigorous examination of how historical forces shape individual psychology. The novel’s central insight, that displacement creates not loss of identity but multiplication of fractured selves, provides a crucial framework for understanding contemporary migration experience within continuing imperial relationships.

While structural flaws prevent the novel from achieving absolute literary perfection, its combination of psychological sophistication, cultural authority, and ideological clarity places it among the most important contemporary examinations of race, displacement, and family trauma. May has written a novel that refuses consolation while insisting on the possibility of survival. Perhaps, it is the most honest form of hope available under current conditions.

The novel’s greatest achievement lies in its creation of Funke and Liv as complete literary subjects whose struggles illuminate broader questions about belonging, justice, and survival without reducing them to symbolic functions. Through their carefully rendered consciousness, May demonstrates fiction’s capacity to bear witness to experiences typically marginalised in literary discourse while maintaining artistic integrity and emotional complexity.