What is a dream? Why do we dream? And, when we dream, with our eyes open or closed, how do we count our dreams or, at least, make them count? Do people in America dream different kinds of dreams?

The ‘American Dream’, coined by American businessman and historian James Truslow Adams in his 1931 book ‘The Epic of America’, tells us that work defines the past and future of the American Dream,a dream of a social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognised by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.

As I sat down to pen my thoughts on dreams and dreaming, my mind raced back to August 28, 1963. One dreamer that the world cannot forget on this day was the civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr., and his dream for America. On this fateful day, at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, he delivered his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech that heralded a new dawn in American history.

Like King Jr., everyone has a dream. But some dream dreams that would never see the light of day, while others dream dreams that change the world. This rare category of people whose dreams leave indelible marks on the sands of time is worth sparing a few words of reflection to make their ‘dream count’.

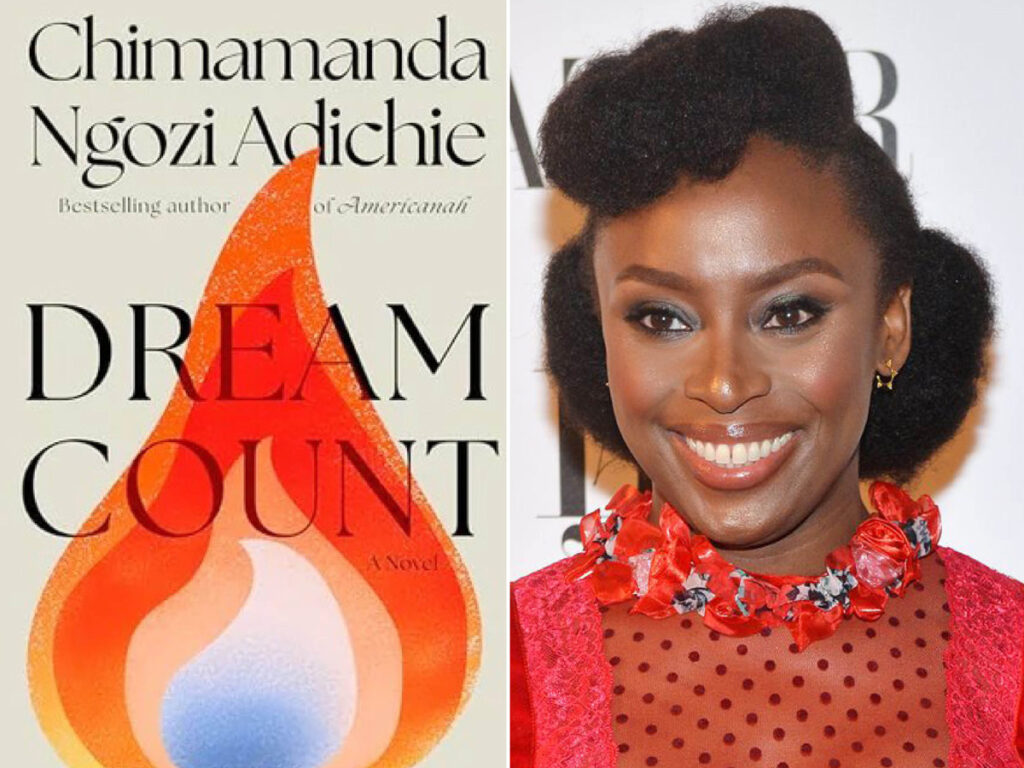

I was excited when I heard that Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie was releasing a new novel after about twelve years of writing her last one, ‘Americanah’. I have often wondered what could have created such a hiatus in her writing endeavours — could it be the burden of being a wife and a mother, or the sometimes-frustrating writer’s block that numbs the creative mind, or the usual thought of quitting writing for a more ‘serious’ career?

I would later learn that the trauma of losing her parents was one of the culprits in the hiatus. On wonder, in a recent interview, after her fourth and new novel ‘Dream Count’ was published in March 2025, she revealed that the book was inspired by her mother, which makes me ponder the connection between dreams and inspirations.

Perhaps it was the same inspiration that made her to, at the age of nineteen, quit the medicine she was studying at the University of Nigeria and travel to the United States of America to study the arts and writing. Perhaps, also, it is some of the fragments of this inspiration and her own version of the American Dream we are seeing in her speeches and books.

For how else could one explain the theme and setting of her ‘Dream Count’ that encapsulates the love and desire to be truly known in a country that promises or advertises love and fame, but offers them on its own terms.

In the book, Adichie gives us a taste of what it means to dream, live, love, and survive in America through the lives of four women — Chiamaka, Zikora, Kadiatou, and Omelogor. The book reflects love beyond societal validation, and intimacy without judgement, seemingly contrary to the ways a typical American society would perceive love and survival, and importantly, in ways they shape a woman’s sense of self in the faces of cultural dislocation, hardship, and trauma, and the ways in which institutional systems fail to protect and support survivors, especially black and immigrant survivors.

The American Dream, through the lens of Adichie’s immigrant women characters, mirrors the resilience and solidarity Nigerians and Africans in the US are known for in their quest to make a living, find love and acceptance, and fit in in a complex society they call home, far away from home.

It is not only through ‘Dream Count’ that Adichie tries to tell us about the American Dream, as immigrants see it. Through her 2009 short story collection, ‘The Thing Around Your Neck’, a moving story, which bears the same title as the collection, tells the story of Akunna, a young Nigerian woman, who wins a visa lottery to go to America to live with her uncle.

From the first sentence of the story, Adichie — without preamble, without mincing words — introduces us to the America of Akunna, who thinks everybody in America has a car and a gun. Her uncles, aunts, and cousins think so, too, and tell her, “Right after you won the American visa lottery, in a month, you will have a big car. Soon, a big house. But don’t buy a gun like those Americans.”

Akunna is full of hope and energy to live the American Dream, but on getting to the country of her dreams and fantasies, she ends up facing complex gender, class, race, and cultural dynamics that make her question her identity. Through Akunna’s story, Adichie teaches us that the promise of a better life in a foreign land often comes with harsh realities in both personal and societal settings.

Chiamamanda Adichie is not the only one who has dreamed, experienced, and written about the American Dream. In the 1960s, poet and playwright JP Clark travelled to America and ended up writing a book — a personal journal and travelogue — titled ‘America, Their America’. In the 1964 book, written while studying at Princeton University, it turned out that Clark’s general experience in America was not what he expected. He not only found that the racial condition in the country was repulsive, but he also clashed with Princeton and was asked to leave the university after a year. This is evident in his attacks on the American middle-class values, from capitalism to Black American lifestyles.

On the other hand, Clark acknowledged that his visit to America was productive, as he reportedly went on to enjoy warm hospitality in the United States, returning as a guest of the State Department, distinguished fellow at the Centre for the Humanities at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, and visiting professor at Lincoln and Yale universities. With grants from the Ford Foundation, he also took a tour of theatres and set up his own repertory company in Lagos.

Another writer and scholar worthy of mention is Okey Ndibe. His 2016 book ‘Never Look an American in the Eye: A Memoir of Flying Turtles, Colonial Ghosts, and the Making of a Nigerian American’ tells his American story before even reading the book.

The book introduces us to the American culture and the differences between Nigerian and American society. He writes about a racial profiling episode that happened between him and a New York police officer shortly after he arrived in America, the death of his father, the day he became a US citizen, and how he met his wife. Ndibe’s experiences, however humorous, reflect serious identity, race, and immigrant experience in a globalised world.

Art and literature are ways through which we seek meaning and solace in the realities of life and society. But, is it possible for a writer to write about dreams, especially the American Dream, as an immigrant, without feeling lost in the dream? How does a writer make their dream or that of their characters count in a world that seeks to stifle their hope and aspirations, in a society that does not recognise their place and talent, and in a country that kills dreams before they are dreamed?

As I pondered these questions, I found a glimpse of hope from a writer who, after reflecting on Clark’s ‘America, Their America’, stated that “Discernment is a gift,” and when a writer possesses it sufficiently, he writes often as a man dancing to the beats of a very distant drum. The writer then adds that it is the truly blessed writer who lives to see his verdict vindicated after the long wait.

“For once, everything about America as discerned by JP Clark when the book was originally written has come to the fore for the whole world to see by the light of time and day,” the writer stated.

This profound submission left me with something more serious to ponder on — the verdict of a dream. James Adams, mentioned earlier, who is believed to have coined the word ‘American Dream’, added what could be regarded as a disclaimer to his stance on the American Dream. He admitted that “It is a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, and too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it.”

Although it has been argued that calling it a “dream” suggests these ideals have not been realised for many Americans or aspiring Americans, it, however, does not reduce its importance as an ideal and a beacon to all nations.

But if the American Dream “is a difficult dream” that can be “grown weary and mistrustful of,” how did Chimamanda Adichie succeed in making it count for herself? Perhaps, the answer is not far-fetched. It is this same ideal that inspired her to move to America, to fight the odds and distinguish herself in America, to show us a glimpse of this dream she has tasted herself, and through the lives of many of her American immigrant characters. Perhaps, ‘Dream Count’ is Adichie’s subtle way of saying “America will break you, but keep dreaming and pushing in spite of the challenges, for success is at the end of the tunnel.” This is what could be perceived as the verdict of a dream.

As I further pondered the verdict of dreams, within the context of African immigrants, my mind raced back to Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. In the speech, King, Jr. reminds his African American people, and by extension, the whole world, of the “fierce urgency of now” and that it “would be fatal for the nation (America) to overlook the urgency of the moment.” King, Jr speaks about not walking alone, and that “as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.”

We have learned from the wealth of Adichie, Clark, Ndibe, and others’ immigrant stories and experiences — as well as those of their moving characters in their works — in their quest to live the American Dream. They have taught us that if we must dream, we must dream big, and if we must dream in America, we must dream even bigger and make it count by keeping in mind Adams’ caution that “it is a difficult dream”, but more importantly, yielding to King Jr.’s charge of marching ahead, without turning back.